Read about Chakmas and Hajongs from Prelims Notes.

Migration of the Chakmas and Hajongs:

-

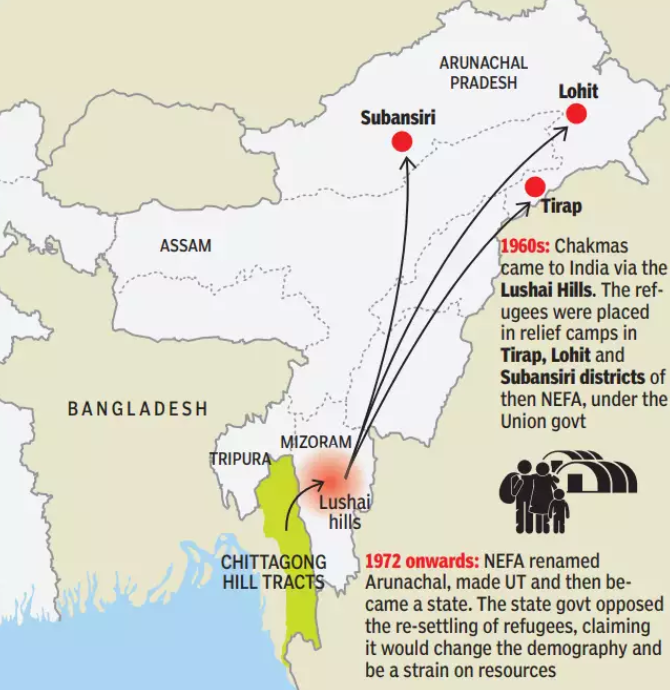

The Buddhist Chakmas and Hindu Hajongs are migrants from the Chittagong Hill Tracts of erstwhile East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

-

They were displaced in the 1960s by the Kaptai dam on the Karnaphuli River and sought asylum in India.

-

A large chunk of these migrants was settled in relief camps in the southern and south-eastern parts of Arunachal Pradesh from 1964 to 1969.

-

A rehabilitation plan was formulated, land and financial aid were provided depending on the size of their families.

-

Mizoram and Tripura also have a sizeable population of the Chakmas.

-

Some Hajongs also inhabit the Garo Hills of Meghalaya and adjoining areas of Assam.

Chakmas and Hajongs Issue:

-

Arunachal Pradesh wants to conduct a “special census” in all the Chakma- and Hajong-inhabited areas of the Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh.

-

Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister had stated that his Government was serious about relocating the Chakma-Hajongs to other States.

Current status of Chakmas and Hajongs:

-

As of 2011, there are 47,471 Chakmas and Hajongs living in the State of Arunachal Pradesh. However, as per the Chakma Development Foundation of India, this number stands at about 65,000 currently. A majority of them live in the Changlang district.

-

Of the total estimated 65,000, 60,500 of the migrants are citizens by birth under Section 3 of the Citizenship Act, 1955, after having been born before July 1, 1987, or as descendants of those who were born before this date. The applications of the remaining 4,500 surviving migrants have not been processed yet.

-

The organisations representing the migrants argue that they were permanently settled by the Union of India in the 1960s and since 95% of the migrants were born in the North-East Frontier Agency or Arunachal Pradesh, the Inner Line Permit mandatory under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation of 1873, for outsiders seeking to visit the State, also does not apply to them.

Concerns expressed by Chakmas and Hajongs:

-

Chakma organisations have termed the proposal for the special census as nothing but racial profiling of the two communities based on their ethnic origin.

-

This they claim violates Article 14 of the Constitution of India (Right to Equality) and Article 1 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination which has been ratified by India.

-

The repeated statements by Arunachal Pradesh officials to get the Hajongs and Chakmas relocated goes against previous Supreme Court Judgments on the issue.

-

The Supreme Court had in January 1996 prohibited any move to evict or expel the Chakma-Hajongs and directed the Central and State governments to process their citizenship. Similar observations had also been made by the National Human Rights Commission.

-

The Supreme Court in its September 2015 judgment had noted that Arunachal Pradesh cannot expect other States to share its burden of migrants.

-

-

Members of the two communities have allegedly been victims of hate crime, police atrocities, discrimination and denial of rights and beneficiary programmes.

Concerns raised by locals:

-

Local organisations argue that the Union government had not consulted the local communities before settling the Chakma-Hajongs.

-

They argue that Arunachal Pradesh is having to carry the burden of hosting the migrant Chakmas and Hajongs.

-

Local tribes claim the population of the migrants has increased alarmingly and could outnumber the indigenous communities. This they claim poses challenges to their own survival given the increased competition over land, resources and jobs.

Threats posed by extreme ethnic consciousness:

-

Though ethnicity and ethnic consciousness are a universal phenomenon, this is considered a unique feature of tribal societies.

-

Such ethnic consciousness in their more extreme forms of expression are exclusion and hatred of the ‘Other.’

-

Manifestations of the same have been observed in the recent attacks on non-tribal people in Meghalaya’s capital Shillong or an Assam-based group’s warning to a fuel station owner in Guwahati against employing Bihari workers.

-

Violent ethnic assertions could bring in divisions within the society. This could take extreme forms of ethnic cleansing and civil wars. Ethno-nationalistic mobilisations could lead to calls for separatism.